On her 80th birthday, Annabelle Whitford was on top of the world. She'd received jams, jellies, flowers, phone calls and telegrams from well-wishers across the country, and had entertained several photographers and reporters who had come to call, all within her small Chicago apartment. It was quite the change from the birthday Whitford thought she would have just a day prior, when the recently widowed former Follies girl felt as though she had been forgotten by the rest of the world. She felt lonely and hopeless, despite being, at one time, one of the best-known dancers in the country.

Annabelle Moore Whitford was born July 6, 1878 to Amanda Moore in Chicago, Illinois. Annabelle's biological father was out of the picture, but it didn't really matter. She and her mother were inseparable, and by the time she was in her teens, her mother had remarried. According to Annabelle, she was on stage by the time she was 11, and began to make a name for herself as a dancer. Her signature dances soon became the

Serpentine, the Butterfly and the Sun Dances, and she soon became so well known (particularly in New York), that she was invited by Thomas Edison to be one of his first subjects to be recorded with the Kinetoscope. Edison's films of her dances became so popular, that she was invited back to the Black Maria to record new performances to make up for the prints that had worn out. Thanks to her growing popularity, she was also chosen to perform at the World's Columbian Exposition (aka the Chicago World's Fair) just months shy of her 15th birthday.

Although her performance at the fair would help boost her popularity even further, she soon found herself in the midst of one of the highest profile scandals to hit 19th century New York. In December 1896, Annabelle said she was approached by agent James H. Phipps to perform at a bachelor party being held by Herbert Seeley, grandson of P.T. Barnum, for his brother. Although Annabelle initially accepted the offer, Phipps told her to dance for the men without her tights. She was insulted, and although he later said she could wear her tights, she refused and told her stepfather, theatrical agent William S. Moore, about the incident. He reported the incident to the police who then raided the banquet where "muscle" dancer Ashea Wabe was performing. Although she wasn't nude at the time of her arrest, Wabe later admitted that she'd been asked to perform nude and that she fully intended to. The trial that resulted from the raid stemmed from public indecency, but because of the stature of the men involved, there was backlash against the police and Annabelle's stepfather. Annabelle herself testified during the trial, and had her testimony refuted by others, but her stepfather ultimately paid the price. On January 17, 1897, Moore died of pneumonia at just the age of 52. His doctor claimed that the notoriety the trial had brought him hastened his death.

In the end, the scandal did little to hurt Annabelle's career. She returned to the stage, pursued drama for a couple of years, and then made the transition into musical comedy where she again began to make a name for herself. She appeared in productions like The Sprightly Romance of Marsac and The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast, before joining Eddie Foy in a production of Mr. Bluebeard in 1903. Although the show was well-received, its run ended in tragedy. On December 30, the company was preparing to end its run at the beautiful Iroquois Theatre in Chicago. The theater was packed well beyond capacity -- 2,000 audience members were estimated in attendance and many of them were children. At the beginning of the second act, an arc light shorted out, causing a curtain to catch fire. A stagehand attempted to douse the fire, but it was no use. The scenery and stage were soon in flames. Foy remained on stage trying to calm patrons as they attempted to escape. Some patrons were trampled by fellow audience members, doors failed to open, and other patrons were trapped in dead ends. Annabelle escaped, but was injured and admitted to a local hospital. Others were not so lucky. An estimated 575 people died the day of the blaze with dozens more dying in the following days. It was an event that Annabelle would never forget, and she would often participate in memorial services marking the anniversary of the tragedy in later years.

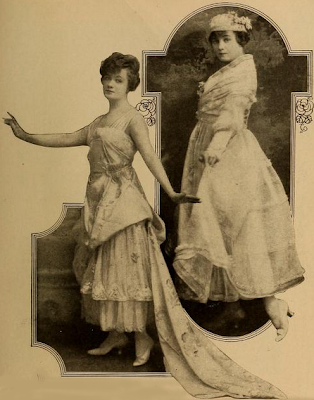

Scene from the Ziegfeld Follies of 1908

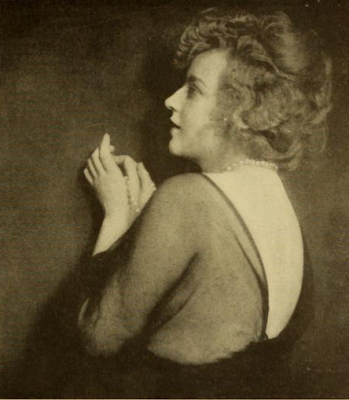

Annabelle's career was about to take yet another turn. Her roles in musical comedies, and her figure, soon got the attention of Flo Ziegfeld himself, and she joined the Follies of 1907. During her run with the Follies, she became a living version of many of the idealized "girl" types of the early 20th century. She often played the Gibson girl, the Christy girl and the Brinkley girl, and sang on stage. She was dubbed one of the most beautiful follies girls ever known, but only remained with the company for three seasons before embarking on her own vaudeville tour. Her career came to an abrupt end, though, when she married Edward J. Buchan, a stage electrician who would later become a surgeon. She retired from the stage and the screen, but continued to be very involved in the Chicago community. She was on the board of the Salvation Army and a member of the Women's War Relief Association.

She also continued to pursue her love for the stage, albeit vicariously. In 1939 she created a Follies-esque review featuring 40 grandmothers and great-grandmothers. Annabelle directed the cast, and the show included musical acts, skits and even a revamped version of the Brinkley girl routine from 30 years prior. Although the beauty Annabelle had embodied was now out of fashion, she didn't hesitate to speak her mind about the new generations' glamour girls. “The Gibson girl didn’t have to have a ‘mask’ of cosmetics, or a scanty costume to be admired; yesteryear’s belle had real beauty.” Even though she was in her 60s, she still only used cosmetics sparingly.

Members of the Women's War Relief Association: Mrs. Edward J. Buchan (Annabelle Whitford Buchan), Mrs. Norval H. Pierce (nee Drucilla Wahl), Mrs. Edward R. Fifield and Mrs. William M. Hight

Annabelle and her husband had a lived a comfortable life together in a spacious home, but it soon slipped through their fingers. She lamented in an 1945 interview that when she agreed to be filmed by Edison she made a terrible mistake. “It was at this time that I made the greatest mistake of my life. For my performance, Mr. Edison offered me my choice of $15 or an interest in his new invention. I took the cash.” She lamented that a colleague had taken the offer of interest and was now a millionaire. Had she made a similar choice, her final years may have been happier. By the '50s, the couple was living off of a government pension of just $114 a month (she had earned $750 a week when she was with the Follies). When she was given the opportunity to pen a remembrance of the tragic Iroquois blaze, Annabelle donated the $900 check she received to a charity for underprivileged Chicago youth. When her donation was discovered, the couple was dropped from the pension program, and the charity was forced to return what was left of the donation, about $480, to the Buchans to live off of until they could reapply for the pension program. At one point, their small apartment didn't even have heat.

Shortly thereafter, Edward died, leaving Annabelle a penniless widow. As her 80th birthday approached, newspapers remembered the star who had fallen on hard times, and interviewed her. “No one comes to see me. it would be wonderful to hear from someone -- anyone, particularly on my birthday,” she told them, and people everywhere responded. Her apartment at 2401 W. Diversey was soon buzzing with activity, and reporters who showed up the day of the celebration were greeted with a joyful Annabelle. “Oh, the telegrams! The letters and telegrams! The reporters! My room is a bower of roses. And look! All kinds of jams and jellies. A Chicago woman brought them. Oh, what a day!”

Although her 80th birthday was a shining moment, it didn't change her impoverished state. She died November 29, 1961 at Augustana Hospital at the age of 83.

A reporter covering the Seeley Scandal once described her as a symphony in yellow hair, and thanks to surviving Edison negatives, we can still watch this symphony in all of her beauty. Watch excerpts from her Butterfly and Serpentine dances below.