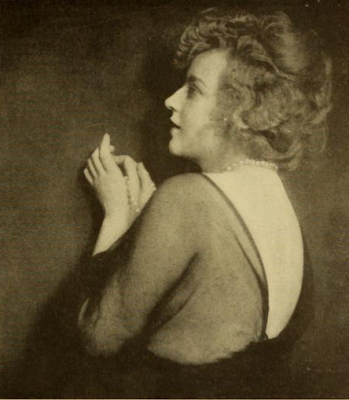

Although she was a popular leading lady with the Chicago branch of Essanay, Edna Mayo’s fame and stardom were brief, as was her film career. She was in the public eye for less than five years, but she made quite an impression, and when she left the industry, fans were confused and wondered where she had gone. Her disappearance and life after film remain a mystery.

Edna Mayo was born in Philadelphia, but the specifics surrounding it are unclear. Although available sources claim she was born March 23, 1895, contemporary magazines claimed a March 27, 1893 birth date, (which gels with the ages and dates cited for major events in her career). She was an only child, and it was said that she was of a famous theatrical family, though none of her famous family members were ever cited in articles. Later, the press would refer to her mother as simply Mrs. J. Mayo.

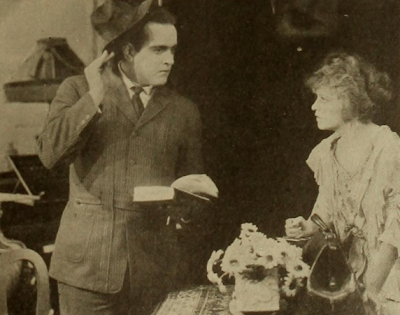

Carlyle Blackwell and Edna Mayo

After graduating from Girls College in 1909 at the age of 16, she pursued stage drama full time. Although she claimed she had been on the stage since the age of 5, her first notable work was in “The Social Whirl” which ran from April to September of 1906. She followed that up with parts in “The Merry Widow Burlesque” (Jan-May 1908), “Girlies” (Jun-Aug 1910), and “Help Wanted” (Feb-May 1914). When she wasn’t on stage, she was pursuing artistic hobbies, as well. She studied sculpture in New York at the Art Students League and, when she later moved to Chicago, she continued to study at the Art Institute.

Mayo made her move from the stage to film in mid-1914, after her run with “Help Wanted” ended. She was signed by Favorite Players to make “The Key to Yesterday” opposite Carlyle Blackwell. That arrangement soon fell through, though, and once the picture was over, she bounced to Famous Players, and even made a film under Pathe. By the beginning of 1915, though, she had set down roots in Chicago, joining the players at Essanay. In February, she made her Essanay debut with “Stars, Their Courses Change” playing opposite Essanay’s leading man Francis X. Bushman, and was touted as their new leading lady. She was quickly paired with the best the Chicago branch had to offer, acting opposite players like Richard Travers and Bryant Washburn.

Henry B. Walthall and Edna Mayo in "The Woman Hater"

Although she was still a relative newcomer to the world of film, she was quite a temperamental star. She had trouble acting with crowds watching her, was self centered, and was determined to have things her way. She talked of pleading with directors, begging, “Let me have my own way. Let me say what my feelings tell me to, and my action will amount to something -- otherwise never.” Although her fits undoubtedly led to some friction on set, it certainly allowed her to put out good work. She worked very consistently throughout the rest of 1915, even appearing in some gender-bending roles (a big deal for a woman who was once declared the most beautiful photoplay actress).

"The Strange Case of Mary Page"

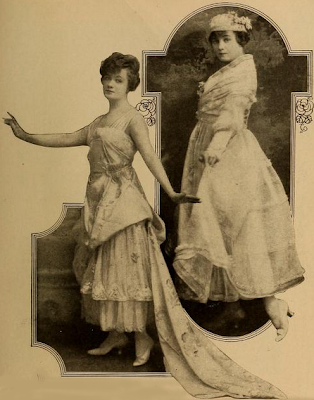

With 1916 came her biggest project to date. The 15-episode serial “The Strange Case of Mary Page” starred Mayo in the title role opposite the great Henry B. Walthall. The plot was intriguing -- Mary Page is on trial for murder, but she and her lawyer/lover are convinced she didn’t commit it -- and audiences responded favorably. The studio got scores of letters every day from fans who were convinced they had figured out the answer for the murder mystery element of the story. The series was quite an undertaking, and represented a first for Essanay, so the PR machine worked hard behind the scenes to make it a profitable endeavor. Ads were taken out in publications like McClure’s, McCall’s, Ladies World, and Pictorial Review to ensure that female audiences knew of it. They also used the elaborate, gorgeous dresses Mayo wore throughout the film as a selling point. The gowns were designed by Lucile, aka Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon, and one piece in particular reportedly carried a price tag of $1,000. If they couldn’t attract female audience members purely on plot, they thought, they might get them because of the fashions.

Edna Mayo wearing dresses created for "The Strange Case of Mary Page"

Mayo bragged that she spent nearly everything she made on clothes, and her wardrobe choices led to magazines declaring her The Best Dressed Woman on the Screen. Though she splurged on gowns, she didn’t lead a luxurious lifestyle otherwise. She divided her time between work and her apartment on Sheridan. She wasn’t married and made it clear that she had no intention of marrying. Not only were all husbands bossy, she asserted, but it would disrupt her routine. “Honestly, I don’t think I’ll ever marry. I’m so happy working, and leading my quiet little life between apartment and studio, studio and apartment. I don’t want to be upset and made unhappy -- even by happiness!”

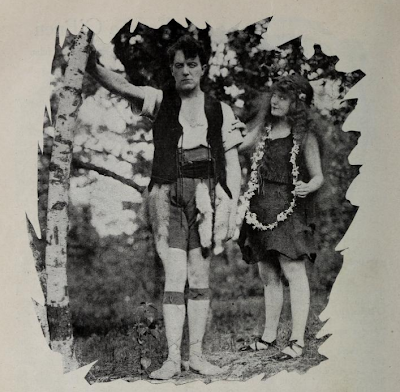

Aside from “The Strange Case of Mary Page,” Mayo’s most interesting project of 1916 was “The Return of Eve,” released in September of that year. It featured Eugene O’Brien and was filmed around the Wisconsin Dells. It told the story of a modern day Garden of Eden, where scientists mounted an experiment that involved raising infants in the wilderness to grow up “naturally.” When the now-grown Mayo and O’Brien are brought back to civilization, they’re horrified and return to their former way of life.

"The Return of Eve" featuring Eugene O'Brien and Edna Mayo

Mayo and O’Brien received praise for their roles, but her acting opportunities began to dwindle. Rumors started to spread in mid-1917 that she had left Essanay, but she brushed them off, speaking instead of doing humanitarian work in the slums of Chicago. By December of that year, however, she was unemployed, and by January she had disappeared from the screen. A year later, she attempted to stage a comeback with the General Film Co. and “Hearts of Love,” but it didn’t work. “Hearts of Love” was her final film.

A couple years prior, Mayo had told fan magazine reporters that she had no desire to go back to the speaking stage, but it’s unclear what exactly she did do following her screen retirement. It seems her fan base and the world of film lost track of her. She appears to have moved back to California, though, and died in San Francisco in 1970.

Although Mayo was by all accounts a formidable actress, we don’t really have proof of it today. Her films are mostly considered lost, and we’re left only with plot synopses to judge her by. Still, we can’t help but hope that a copy of “The Strange Case of Mary Page” will miraculously reappear for film fans and historians alike to enjoy.

Jump over to my Pinterest page to see more of the ads for "The Strange Case of Mary Page" and other Edna Mayo pictures.