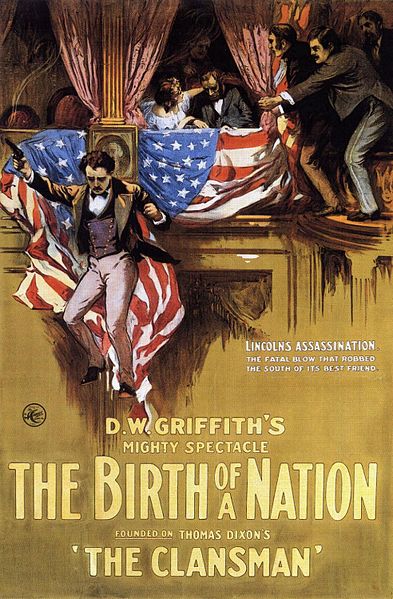

We return, as we will often do in this blog, to D.W. Griffith. Rather than examine another epic work of cinema, like "The Birth of a Nation," we, instead, turn to Griffith's days at Biograph. "The New York Hat" was made and released in 1912, four years into Griffith's incredibly prolific career. The film is simple and straightforward and charming. Although it is nowhere near Griffith's best work, it is notable for a number of reasons.

A Bit of Background

Griffith made his directorial debut in 1908 with a little film called "The Adventures of Dollie." Incredibly, this film has survived to this day (you can watch it here). Griffith had not dreamed of becoming a director. He had tried his hand as a playwright (out of his love for writing) and an actor (out of the need to make ends meet), but when one Biograph director became indisposed, and Biograph found itself in need of another director, Griffith took advantage of the opportunity. The result was at least on par with many of the films that had been produced by Biograph up until that time. Impressed and pleased with his own work, Griffith quickly became one of the most prolific directors at Biograph and, truly, its most visionary.

From 1908 to 1913, Griffith directed more than 400 films and established a close relationship with cinematographer Billy Bitzer, with whom he introduced enormous advancements in the art of film. It was also during these years that Griffith discovered and worked with some of film's biggest future stars. A number of them are even present in this film.

|

| Mary Pickford |

'The girl with the curls,' Mary Pickford, one of the screen's first and biggest stars, was one of Griffith's earliest and greatest discoveries. "The New York Hat" marks her final Biograph picture, but Pickford's friendship and partnership with Griffith would endure, leading to the formation, with Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin, of the production company United Artists.

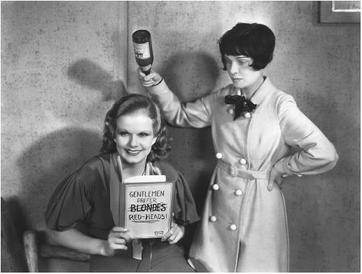

Also appearing in "The New York Hat" is Lionel Barrymore, who had joined Biograph in 1911. Although they do not appear in named or prominent roles in this film, we are also given a glimpse at some future Biograph stars, namely Lillian Gish and Mae Marsh. Another individual worth mentioning is the film's screenwriter, a then relatively unknown Anita Loos. If you don't know Loos by name, you certainly know her by her work. Among other screenplays and works of fiction, Loos penned "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes," "Red-Headed Woman" and "Gentlemen Marry Brunettes." Loos' talents would also be utilized by Griffith in 1916 to pen the titles for his epic follow-up to "The Birth of the Nation," "Intolerance." "The New York Hat" was one of Loos' first screenplays and doesn't bear much resemblance to her later works, but it certainly brought Loos her first big break and set the ball rolling for her as a screenwriter.

|

| Jean Harlow with Anita Loos |

The Story

Mary Harding, on her deathbed, leaves her pastor (Lionel Barrymore) with one request, that he use the trust she leaves to him to treat her daughter Mollie (Mary Pickford) to the "bits of finery" which her husband had constantly denied her and Mollie. Her only request is that he tell no one. The pastor takes this request to heart.

|

| The Pastor (Lionel Barrymore) reads Mary Harding's final request |

Some time after, Mollie prepares to go out into the town, but upon examining her appearance, she hesitates. Her jacket is shapeless, the sleeves are too short and her hat is rather plain and old. She appeals to her father, asking if she can have a new hat. He, predictably, denies her request, leaving her to make do with her appearance and wardrobe.

Whatever confidence she has instilled in herself prior to leaving her house is diminished when young women giggle and draw attention to her shabby, simple appearance. Like the other women of the town, Mollie soon finds herself down at the hat shop admiring the latest import from New York. Mollie encounters the pastor here, and he observes her lamentation that she cannot have or afford such a beautiful hat.

|

| "Daddy, can't I have a new hat?" |

|

| Mollie (Mary Pickford) goes downtown, leaving her shabby hat behind |

|

| Mollie admires the new hat in from New York |

Mollie leaves the shop brokenhearted. Remembering his promise to Mary, the pastor enters the store and purchases the hat, causing the town gossips to speculate. Hatbox in hand, the pastor finds Mollie at her home and leaves her with her present. In a beautiful little sequence, Mollie experiences a series of emotions, from astonishment, to joy, to sorrow.

|

| The town gossips speculate |

|

| Mollie's range of emotions...from joy |

|

| ...to sorrow and feeling overwhelmed... |

|

| ...to pride |

Taking pride in her appearance, Mollie wears her New York hat to church, causing a fuss among the gossips and church board members. Believing that Mollie and the pastor are having an affair, Mollie's father destroys her beloved hat, causing Mollie to seek refuge and sympathy from the pastor. In the climax, the pastor and Mollie are confronted by the town gossips, the church board and Mollie's father. The pastor assures everyone that his intentions were pure, showing everyone involved Mary Harding's final request to him.

Satisfied and, perhaps, annoyed by the pastor's explanation, the gossips and board members take their leave, leaving behind the pastor, Mollie and her father. The pastor has one final request, however, to have Mollie as his wife. Mollie shyly and giddily accepts his offer as the end intertitle card appears.

The Result

A Broadway veteran at this point, it is interesting to see Lionel Barrymore at this stage in his career. Just 34, Barrymore was a newcomer to film and attempts to be bridging the very different worlds of stage and screen acting. Pickford, however, was a film veteran at the age of 20 and her expertise in the realm of screen acting particularly shines in this film. Pickford's beautifully emotive face adds so much to the film, even if the story itself is quite simple.

It is because of the talent of Griffith, Pickford and other Biograph players that the Biograph company became the top studio at the time. As Lillian Gish recalled in the documentary "Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film," everyone copied Biograph. The desire to be as popular as Biograph made piracy a legitimate threat. In order to preemptively prevent such theft, Biograph, like other studios, made a point to conceal its logo within the scenery.

To glance at the following frame, one might think that the blocking and framing is rather curious. Such extra space would suggest that someone else would be joining Pickford in the scene.

But upon closer examination, we see Griffith and Bitzer's reason -- by placing Pickford at the right side of the screen, the Biograph logo (AB for American Biograph) is cleverly placed in the background at the left side of the screen.

By placing studio logos in the scenes and intertitles themselves, competitors were unable to steal them and use them as their own.

But upon closer examination, we see Griffith and Bitzer's reason -- by placing Pickford at the right side of the screen, the Biograph logo (AB for American Biograph) is cleverly placed in the background at the left side of the screen.

By placing studio logos in the scenes and intertitles themselves, competitors were unable to steal them and use them as their own.

Is "The New York Hat" as action-packed or dramatic as his other works of the period? No. But it is worth the watch for its sincerity, its sweetness and its featured players.

You can watch "The New York Hat," featuring the young and handsome Lionel Barrymore and the beautiful Mary Pickford, in its entirety below.