Although you may not know the name Carl Laemmle, you undoubtedly know the studio he helped create -- Universal Pictures. Laemmle came to the U.S. from Germany in 1884 and settled in Chicago where he worked as a bookkeeper for 20 years. As nickelodeons grew in popularity, he got involved in the world of film, creating International Motion Pictures (IMP) in 1909 and Universal Pictures in 1912. Universal Pictures is now the oldest movie company in the U.S., and the second oldest company still in production in the world (the first being Gaumont). Of course, Universal didn’t become successful by chance. The studio's success was due to a bit of Laemmle Luck, in the form of a combination of respected actors, great storylines and effective advertising.

Laemmle was a master of promotion. IMP was one of the first studios to credit and promote its stars by name, which helped make them household names. It also used those names, and the public’s adoration of them, to create effective publicity stunts and advertising campaigns to drum up more interest in the studios. One of the actresses most often used in these campaigns was Florence Lawrence, also known as the IMP girl.

Lawrence was one of the first true movie stars, so when a rumor surfaced that she had been involved in a horrific fatal accident with a street car, the public was distraught and heartbroken. Shortly after that, an ad began running in trade papers and newspapers that debunked the rumor, calling it a cowardly lie. It also mentioned that Lawrence would be appearing in a new IMP film very soon.

In truth, the rumor was created by Carl Laemmle himself as a publicity stunt.

Although Lawrence worked for several film companies during her career, whenever she returned to Laemmle, he made sure to take out ads for it in the trade papers. During one of her first returns, Laemmle took out a full page ad that was constructed as a letter from Lawrence to the theater owners that exhibited Universal films.

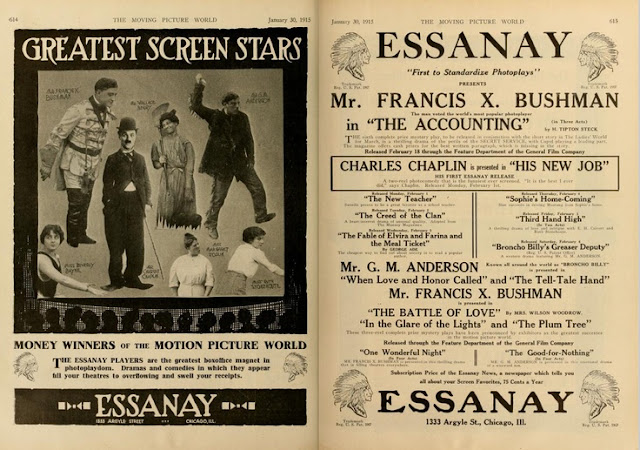

When she began to approach the end of her career, Laemmle staged Lawrence for a comeback, using a clever technique that involved purchasing multiple pages of advertising in the trade papers that alluded to a comeback, without giving away all of the information at once. The first ad ran in the January 1, 1916 issue of Moving Picture World, and acted as an effective lead-in to the ad that ran the following week.

Laemmle then adapted this technique for his next attempted comeback with fading child star Ethel Grandin. This time, he spread the advertisements out over three weeks, with the first appearing in the February 26, 1916 issue of Moving Picture World.

For more of these great vintage ads, check out my Pinterest board devoted to silent film ads.