Helen Gardner was a pioneer in a lot of ways. Not only was she the first American film actress to form her own production company, she was also the among the first filmmakers to embrace making features, and was the first vamp on screen. Yet, she has been forgotten and overlooked. Perhaps her relatively short career in the earliest days of the studio system is to blame, but the strides she made as an actress and producer should have given her a more prominent place in film history.

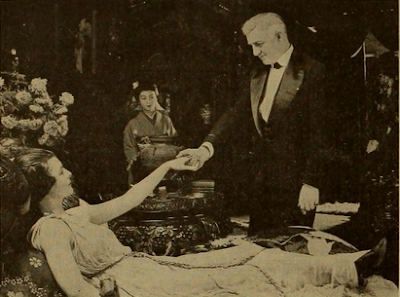

John Bunny with Helen Gardner in "Vanity Fair"

Gardner got her start in film in 1910 when she was signed to New York’s Vitagraph Company-- one of the preeminent studios in the early days of film. Not only did it have the likes of Maurice Costello (father to Dolores Costello) in its ranks, it also helped silent legends like the Talmadge sisters get their start. It didn’t take long for Gardner to start getting noticed by critics and fans alike. In 1911, she starred in Vitagraph’s adaptation of “Vanity Fair” along with America’s preeminent comedian at the time, John Bunny (the first in a long line of lovable, chubby male comedians), and garnered praise for her portrayal of Becky. Her forceful and expressive style helped her stand out from the rest of the cast and caused many moviegoers to ask fan magazine writers about her.

This admiration and critical praise could have been the spark to push Gardner to form her own production company. By 1912, she had formed the Helen Gardner Picture Players (later the Helgar Corporation), with Charles Gaskill directing, and Gardner having final say over most aspects of her films. Not only was she the producer, she was also the scenarist, editor and costumer designer. The Gardner Picture Players remained in New York (Fort Lee, New Jersey was Hollywood before Hollywood), moving the company to a new residence at Tappan on the Hudson. The company came out of the gate strong -- their first production was “Cleopatra” and it helped cement Gardner as a powerful actress who excelled at playing exotic, vamp characters.

Gardner followed up “Cleopatra” with films like “A Daughter of Pan,” “The Wife of Cain,” “A Sister to Carmen” and “A Princess of Bagdad.” Although the films generally got good reviews, and the Gardner Picture Players marketing team promoted them throughout the pages of trade magazines, money seems to have been an issue. The company very publicly split from Warner’s Features distribution, with the major point of contention being money owed to the production company from Warner’s, and found a new distributor, but the company folded in 1914. Gardner returned to Vitagraph shortly thereafter, but had retired from the screen by 1916, returning to film only a few times in the 1920s. She died in Orlando, Florida in 1968.

The collapse of smaller independent production companies was not unusual in the early days of film. Thanks to lawsuits and patents, Thomas Edison had done a hell of a job threatening smaller production companies still located on the East Coast into submission, and spurring others to make the jump to California. It was because of this constant legal threat that companies like

Essanay and, yes, Vitagraph, approached Edison and formed the Motion Picture Patents Company. Although it saved them from legal action and kept them in business, it also severely restricted the length of films they were allowed to make. Did this cramp the creativity of the companies' filmmakers? Undoubtedly. But did it help control costs and keep their work profitable? Definitely.

I suspect that Gardner's early embracing of the feature film, and her desire to create them exclusively and independently, resulted in financial troubles for the company. To put the 1912 release of "Cleopatra" in context, it took until 1914 for the MPCC to allow members to create feature releases. D.W. Griffith's first feature, "Judith of Bethulia," and Mack Sennett's first feature-length comedy,

"Tillie's Punctured Romance," were both released in 1914 -- two years after "Cleopatra." Although the features were accepted and praised, Gardner's team was coming from a very different production system. Vitagraph, Gardner's former studio, was known for its prolific output, and in the early days of silent film, quantity tended to overshadow quality. Studios and production companies regularly boasted the number of films they could produce in a week in the hopes of attracting more theater owners. In 1913,

Flying "A" Studios (the American Film Manufacturing Company) were promising three California-made films a week. Compare that to the dozen or so films Gardner put out between from late 1912 (the release of "Cleopatra") to 1914. She was also dealing with independent distributors, and the fact that Gardner and fellow actress Marion Leonard were so vocal about their split with Warner's suggests that there may have been some shady practices going on. Unfortunately, this isn't surprising.

Even when features became common for American filmmakers, studios couldn't afford to make them alone, nor could they make each production an artistic triumph. They had to rely on potboilers -- shorter films that were often made quickly and cheaply with the sole purpose of making money. Big stars and big production companies also used the system to help their audience satisfied while they worked on super productions that required more time and more effort. Gardner's company didn't. They had committed themselves to producing epic, artistic films starring Gardner that were of at least four reels in length. They also held themselves to a higher standard, saying that they were addressing "themselves more particularly to enlightened people -- who even now make up the larger part of all respectable picture theatre audiences, and who complain loudly at the nonsense drooled out to them by the trusts" (aka the MPCC). (It's worth noting that this release stating Gardner's new company's objective was placed directly beside a tradepaper ad for five films Vitagraph had released that week alone. Coincidence?) Did shorts and potboilers count as that "nonsense" being "drooled" out? The company's ambition was admirable, but their self-imposed restrictions gave them a major disadvantage.

The demise of the Helen Gardner Picture Players may not be much of a mystery, but again we are faced with the question of her obscurity -- why has her pioneer status been so widely forgotten? She created her own production company before Mary Pickford, but Pickford’s is the one that's remembered. With her production of “Cleopatra,” Gardner beat Theda Bara and William Fox to the punch by years, yet we’re more intrigued by Bara’s lost super production than we are by Gardner’s extant film. Both Gardner and Bara were praised for their turns as the Egyptian queen, with critics proclaiming each woman was the queen reincarnated, but it’s only Bara’s kohl-rimmed eyes and exotic presence that has managed to survive through posters and pop culture. Gardner’s acting certainly seems to be on par with the greats of the era, and her efforts behind the camera are equally respectable...so what gives?

For what it’s worth, Gardner’s daughter,

Dorin Gardner Schumacher is trying to keep Gardner’s memory alive. Although she never knew Gardner (Schumacher’s mother was estranged from Gardner), Schumacher is trying to piece together details of Gardner’s life into a cohesive biography and memoir. Will this help bring Gardner back to the consciousness of film fanatics? Perhaps if Schumacher staged screenings of Gardner’s existing films, including “Cleopatra” and “A Daughter of Pan,” it might help stir up renewed interest in the screen’s first vamp.